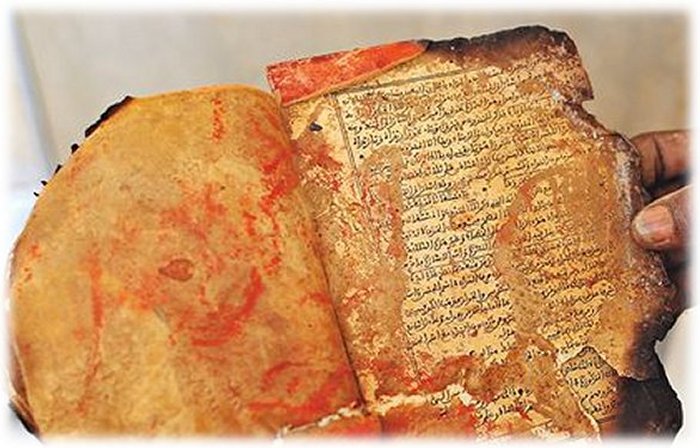

He had a dozen brothers and sisters but in the will his father made him the heir to the family book collection, which numbered in the thousands at that time. So Abdel Kader grew up around these manuscripts. His father ran an Islamic school in the oldest quarter of Timbuktu. Give us a character sketch and describe his extraordinary efforts to collect the manuscripts together.Ībdel Kader Haidara is the son of a scholar from Timbuktu. The hero of your book is a man named Abdel Kader Haidara. Nobody knows how many manuscripts were in the city at its peak but it was almost certainly in the hundreds of thousands. So huge libraries were created, numbering in the thousands of volumes. They would be copied by scribes and accumulated both in the universities and in private homes. Because it had this long scholastic tradition, Timbuktu also had a great literary tradition: powerful Timbuktu families measuring their importance by the books they accumulated on Greek philosophy, poetry, love stories, guides to better sex, astronomy, traditional medicine, as well as the religious books. At the same time, you had these wealthy families that valued learning. Many of the universities were operated out of mosques, so you had a lot of books and manuscripts being created for the scholars. Timbuktu was a university town during its golden age. Explain this unusual provenance-and how it helped preserve them.

The manuscripts were not kept in an archive, but by individual families. Shrines to Sufi saints were destroyed whippings and amputations were carried out in the public squares of the city and, of course, the manuscripts were threatened. They imposed sharia law and began to destroy every symbol of moderate Sufi Islam that almost all residents of modern Timbuktu subscribe to.

In the chaos of the uprising against Qaddafi, the jihadists raided the armories of Libya, took the weapons into Mali, and quickly swept across the northern part of the country, occupying all of the major towns in the north, including Timbuktu. This earned him the nickname “Mister Marlboro.” He was also a cigarette smuggler, who made millions by dominating the cigarette trade across the Sahara up into North Africa. Another leader was Mokhtar Belmokhtar, an Algerian jihadist who had been hardened fighting in Afghanistan and fallen in with some of the most notorious international jihadists. Talk about its rise-and its fanatical leader, Abou Zeid.Ībou Zeid was one of a triumvirate of jihadists, probably the most brutal of them, who took over northern Mali between January and April in 2012. So you had a thriving commercial center side by side with a Cambridge/Oxford-like atmosphere of fervent scholastic activity.Īl Qaeda in the Islamic Magreb swept to power in Mali. At the same time, you had this academic tradition. Several of the great travelers of the Renaissance, in the 15th-16th centuries, passed through Timbuktu and described it as a thriving commercial center with camel caravans and traders on boats on the Niger River bearing everything from linens and teapots from England to slaves and gold out of the rain forests of Central Africa. Put us on the ground during its golden age. Timbuktu has become a byword for the farthest corner of the earth. But it was once an important cultural and artistic center. Speaking from his home in Berlin, Joshua Hammer, a former Newsweek bureau chief in Africa, recounts the tale of The Bad-Ass Librarians of Timbuktu: And Their Race to Save the World’s Most Precious Manuscripts-and explains how the Timbuktu manuscripts disprove the myth that Africa had no literary or historical culture, why Henry Louis Gates had an epiphany when he saw them, and why the jihadists found them so threatening.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)